The Top 10 “Stay-The-Sames” of 2024

January is famous for two things: diets and trend reports. As sure as night follows day, inboxes and LinkedIn feeds will be clogged with the top X trends for the year.

Some of these reports will be good. Some will be bad.

All of them will mention “gut health”.

Their usefulness is debatable. If I were being unkind, I would say that you can pretty much fish around for trend reports until one validates something that you’re already doing/want to do. But let’s leave that debate at the door.

Whether you’re a big-believer in them or not, it’s undeniable that they are positioned as important inputs into business strategy.

However, there is a huge variance in what authors classify as a trend. Fear not - this article is not a boring attempt to define a trend! But I will suggest that there are two main schools of thought - that a trend is either 1) something that has become relatively established, and likely quantifiable in some way via data collected over time; or 2) an early signal of something potentially very exciting/novel/different.

You can see how this gets pretty problematic pretty quickly. The above two interpretations are fundamentally different. One is a collection of things that may have been happening for years; the other is guessing the future based on some early indicators. It’s therefore not straightforward at all as to how and when to use them.

What *is* straightforward is to say trend reports are largely based on the concept of “change”.

Change is sexy. It’s easy to sell. It allows people to create a sense of urgency, or panic. Don’t be Kodak! Don’t be Blockbuster!

But do we think too much about change? Do we exaggerate it because we know it sells? Because it allows us to say interesting things more frequently?

I really do not want to make a habit of quoting Jeff Bezos. Nevertheless, there is a quote attributed to him which has stayed with me since I first heard it:

“I very frequently get the question: ‘What’s going to change in the next 10 years?’. I almost never get the question ‘What’s not going to change in the next 10 years?’. And I submit to you that the second question is actually the more important of the two, because you can build a business strategy around the things that are stable in time. ”

— Jeff Bezos (maybe)

Wise words from the PowerPoint-hating weirdo. Thus, without further ado (and in no particular order), I am pleased to share with you the Top 10 “Stay-The-Sames of 2024:

1. Many people will have healthy aspirations but most will fail.

If people managed to hit their health targets in a sustainable way then relatively few people would have health goals in January. But we already know that the sales of healthy foods and gym memberships will soar. I know this makes me sound like a doomsayer, but it’s going to be a lot more common for people to fall short of their aspirations than to meet them. We tend to focus on what people consider to be a relevant/appealing form of health (e.g. protein, fibre, “balance”), but overlook that it’s bloody difficult to stick to any healthy regime regardless of the specifics. More thought should be given as to how to help people maintain their aspirations rather than trying to pinpoint what the vogue form of health is (clue: you can’t go wrong with weight).

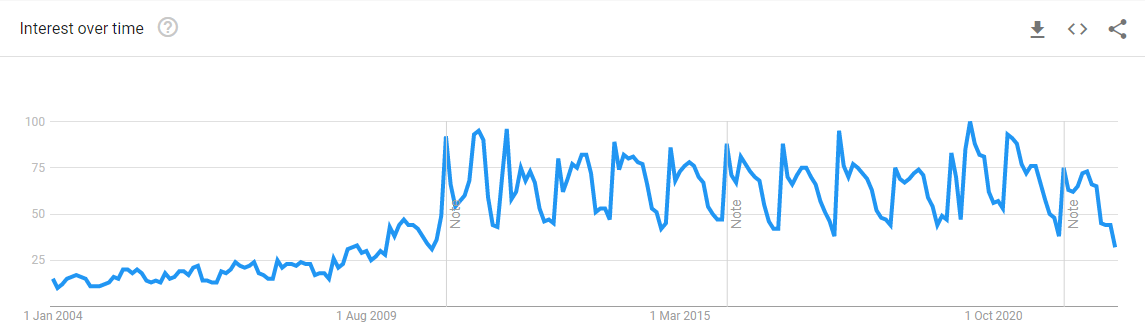

“Lose weight” Google searches. We spike in January (New Year’s Resolutions) and rebound a little just before the summer holiday season. Otherwise, it’s a falling off the wagon throughout the year. Humans are notoriously bad at maintaining healthy behaviours. We give up and start again at a convenient later date.

2. Convenience (and price) will top ethics.

On the face of things, we like to feel like we support the little guy. But, on a macro level at least, we have shown ourselves to favour other things far more strongly. It’s why the supermarkets managed to overpower the independents, and it’s why the likes of Amazon are contributing to the death-spiral of the high street. Plenty of us know in our bones that we probably shouldn’t be making a billionaire any richer, and that we shouldn’t be complicit in the extremely difficult working conditions of warehouse staff and delivery drivers - but it’s incredibly convenient, isn’t it? I’m not proposing you shun ethics! But do consider that ethics alone are not that appealing if they don’t meet the other fundamental desires.

3. Most information on FMCG packaging will go unread.

There are a great many reasons why people buy the groceries that they do. Again, the main ones are entirely predictable: price, promotion, trusted brand. If we re-evaluated every decision every time we stepped foot in a store, we would never get home at the end of the day. Our brains would break. On top of these decisionmaking shortcuts is the way that human being shop in general - autopiloting around the store, fiddling with our phones, or wrangling the kids. Very little packaging label info will ever be read, even less retained. Do not rely on it to communicate everything you need to communicate, and certainly don’t expect that the shopper now knows what you want them to know simply because the words are technically right in front of them.

This woman is scrutinsing the boring label of a product and looks suspiciously delighted to be doing so, but remember that she is posing for a professional photo.

4. People will do their grocery shopping in-person.

Virtually £9 for every £10 spent in UK grocery happens in-store, and this is *after* the nuclear impact of lockdowns, which could barely have been more conducive to online grocery shopping. It is totally understandable why people would buy clothes or toys or books online - there is rarely an immediate need for the item, and returns are very straightforward. However, a good amount of food and drink is bought for consumption within a few days. The tactile element - being able to see and feel and smell - will always be important to people. And in-store benefits such as being able to find the best use-by dates remain compelling. Online shopping is changing some of the dynamics of grocery retail. But let us not pretend that it’s bigger than it is, nor that it will eventually dominate the scene. The retailers are doing it begrudgingly, and a vast majority of people want to shop in-store. The economics don’t really stack up. So what do we expect is really going to drive much more growth? Let’s place some focus on how to make stores the most engaging, convenient, delightful experiences possible.

5. Retailers will miss out on value because of the limit of what a person can carry.

One of my main takeaways from Paco Underhill’s seminal Why We Buy is that many stores under-appreciate the value of getting a trolley or basket in the hands of a shopper. As most shopping happens in-store (see above), we are limited by our carrying capacity. Lots of people walk into a store for a pint of milk and loaf of bread and end up leaving which a bunch of extra stuff (be it chocolate, coffee, or - if you’re in an Aldi - a chainsaw). We can only do that if we can carry it. So to not make it as easy as possible to pick up a shopping basket is unforgivable. Throw in other macro factors such as more convenience store shopping (less car parking, and therefore more people carrying shopping home) and an aging population (less physical strength) and you have something that will never change. As a species, we are not suddenly about to develop a limitless capacity to carry stuff. As Underhill states - there should be baskets at the end of each aisle. Staff should be handing baskets to people who don’t have them. If we don’t help the shopper, we’ll leave money sitting on the shelves.

6. People will find scarcity a better reason than premium cues to spend extra money.

It’s not *that* difficult to get people to pay £15 for a Full English Breakfast in an airport. The provenance of the sausage does not need to be showcased. The ethics of the eggs involved do not need to be proven. The economical mechanics are easy to understand. And yet in other environments (such as supermarkets) we seemingly forget that scarcity (either genuine or perceived) is a powerful lever, and instead we try to do all our price justifications through quality. Not only does this ignore a consistent fundamental of shopper behaviour, it’s going to get even more difficult over time as the quality of even the most basic products tends to satisfy a majority of people.

7. People will be drawn to large portions.

Our tendency to overestimate how much food we need is hardwired. My mum is in her 60s and is yet to prepare a portion of pasta that wouldn’t feed an imaginary five extra guests. Whether our eyes are bigger than our bellies or not, we like to err on the safe side when it comes to portions. Of course, cost of living may mean more careful portioning or only being able to afford smaller sizes. But do not underestimate our “oh go on!” nature. It can be tempting to think that everyone in the UK eats tapas-style and we all share delightful finger foods like we’re at fancy restaurants. But in reality we are a hungry nation that likes big plates full of food. Dare I even say quantity over quality?

8. Cookbooks will be left unopened.

This links very closely to the opening point on health. Our desire to feel like the kind of person who cooks delightful meals from beautiful cookbooks greatly exceeds our willingness to actually do it. As with online grocery shopping, lockdown created a set of dynamics that were extremely favourable to scratch cooking, and the boom lasted a matter of months. My prediction is that the level of scratch cooking in the early months of the 2020 lockdown is a ceiling that won’t be exceeded in my lifetime. Around this time, I ran a small piece of research comparing cookbook ownership to cookbook usage. The knowing smiles and laughter within whatever room I’ve ever presented this research in gives me confidence that this is a pretty universal circumstance - many of us love to buy a cookbook, but oftentimes all it does is make the kitchen look a bit prettier.

Definitely makes the kitchen look cooler. But actual usage is optional.

9. Snacking will cause guilt, but that’s fine.

Snacking is one of those things that many are permanently convinced we are doing more of, even though by now this would mean snacking about 25 times a day. Sometimes snacking increases, sometimes it decreases. It’s very hard to describe either as a trend any more. There has certainly been a movement towards more healthy snack options (and HFSS will likely give this a helping hand too), and it’s easy to see where the insight has come from - snacking is generally unhealthy, and therefore healthier options appeal to “the health-conscious consumer”. Except, let’s face it, there have always been healthy snacking options available, haven’t there? The issue is not one of options - it’s of will to eat. Plenty of people snack unhealthily because that’s what their bodies and brains crave. They may feel a little guilty after a bag of crisps or a bar of chocolate. But this is clearly priced into their behaviour, because they keep doing it! The launch of a vegan, gluten-free protein ball is not going to change that. And that’s OK!

10. Calorie counting will be the most common form of healthy eating.

For as long as I can remember, the narrative around healthy eating is that calorie-counting and dieting is as dead as the dinosaurs. And it’s nonsense! Yes, it’s undeniable that there is a greater appreciation of the multitude of aspects that comprise of healthy living - not just healthy eating but exercise, sleep, personal connections, and so on. But to speak to some people in the industry, you would think that nobody is ever on a diet any more, or that nobody ever tries to cut down on calories. (Or, at the very least, that the youngest person in the country still embarking on this kind of behaviour is 80 years old.) Our weight is, quite simply, the most widely-acknowledged proxy for our dietary health. It’s an actual KPI! The advent of digital food logs/trackers has been in large part because it’s made it easier for us to understand our calorie intake and to set targets. Rather than assume that calorie counting is yesterday’s old news, try to focus on how to make it as easy as possible to do (and maintain). Because in 10 years time it will *still* be the most instinctive way of managing our weight.

It’s hard not to come across as cynical with quite a lot of these. This isn’t the intention at all - it’s simply my interpretation of human behaviour. Some of it involves basic human “fallability” (i.e. one of the things that makes us human!). Others are more geared around an industry that seems to have forgotten a few simple truths (or has rallied around an alternative narrative for its own benefit).

Although businesses need to solve problems in order to succeed, it can be remarkably difficult to pinpoint those problems. We can become addicted to the idea that consumer problems are “ever-changing”. Some things *are* changing. But there are plenty of things which aren’t really changing, which we *still* haven’t nailed. Let’s not forget about them!